This is a transcript, for the video found here:

Bullets:

China is shifting its supply chains for agricultural products to Russia and South America.

Over $12 billion in US farm exports to China is at risk. There are no outstanding orders for American ag to China for the rest of this year, and that demand is being met by booming exports from Brazil and Argentina.

US trade officials are scrambling to sell to new markets in Europe and Asia, but the high tariffs on other industries are also pushing buyers to Brazil.

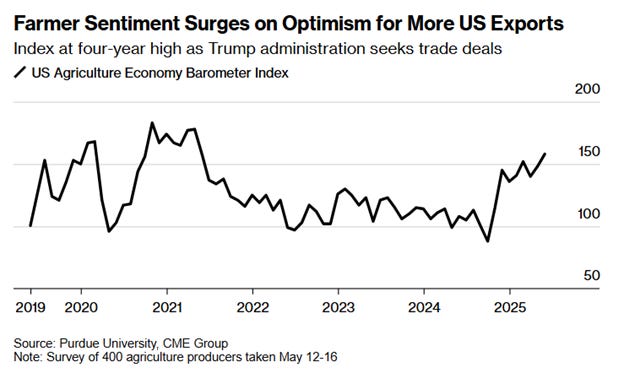

Despite vanishing export markets and falling commodity prices, American farmers report high levels of optimism.

Report:

Good morning. This is a mystifying headline, that US farmer sentiment is at the highest level in four years. A skyrocketing number of farmers expect a strong recovery in agricultural exports over the next five years.

The Agriculture Secretary is going around the world, trying to open new markets for American farm products, like wheat and soybeans, to Italy and elsewhere. Secretary Rollins is barnstorming other countries to find new partners for trade.

The problem is here: China isn’t buying anything coming off of US farms, unless at a last resort. As of now, China—who are the world’s largest buyers—have no outstanding orders for American corn, soybeans, or wheat for the rest of the year.

Here we see the problem if Chinese buyers stop buying from US farms—in 2024, 49% of US soybean exports went to China, meat and poultry was another 13%. And 2024 was already a steep decline, from previous years.

This is a massive shift, in a short time, for supply chains—a more than 12% drop in just a single year, shifting from Western countries to Latin America. Those are big pieces of the pie, and so now our trade officials are scrambling around the world, trying to find new markets that can replace Chinese demand—visits are scheduled to Japan, Vietnam, India, and Peru.

Chinese supply chains are moving, and demand satisfied by imports from Russia—which is massive, and we don’t even know how big it is because all of that trade is overland, and off of our exchanges. And China is also stepping up their imports from Brazil and Argentina. China recently signed a deal for $900 million worth of new Argentine food exports--soybeans, corn and oils. China is already Argentina’s largest buyer of soybeans, and they are sourcing more of their ag buys from South America.

Brazil and Argentina are well-positioned in the trade war between the US and China. Farmers there expect to get all the business that would have otherwise gone to US farmers, come harvest time later in the fall. The United States is the world’s biggest supplier of farm products, and China is the world’s biggest consumer of them. So we see the strategies here, being employed by both sides: China needs to find new suppliers to replace what was coming off of American farms, and the United States needs to find new buyers to replace what China is now growing themselves, or buying from Russia or South America.

These are prices for soybeans in producer markets. In the United States, soybeans are up just slightly, 2% or so from the beginning of the year. But in Brazil—black line, and Argentina in red, prices are moving solidly higher, all on the back of new Chinese exports. Farmers in Brazil and Argentina are making more money for ton, and moving higher volumes.

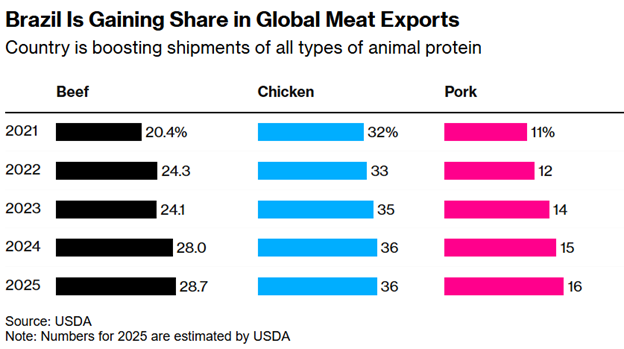

We’re seeing the same play out in meat markets, where Brazil is ramping up and is now a major global exporter of beef, chicken and pork—just steady increases, in all of them.

And that will accelerate as well—our tariffs are hitting our trade partners in other industries, and they are turning to Brazil to replace US meat producers. Algeria and Turkey are buying more Brazilian beef, and now the Japanese are looking to buy.

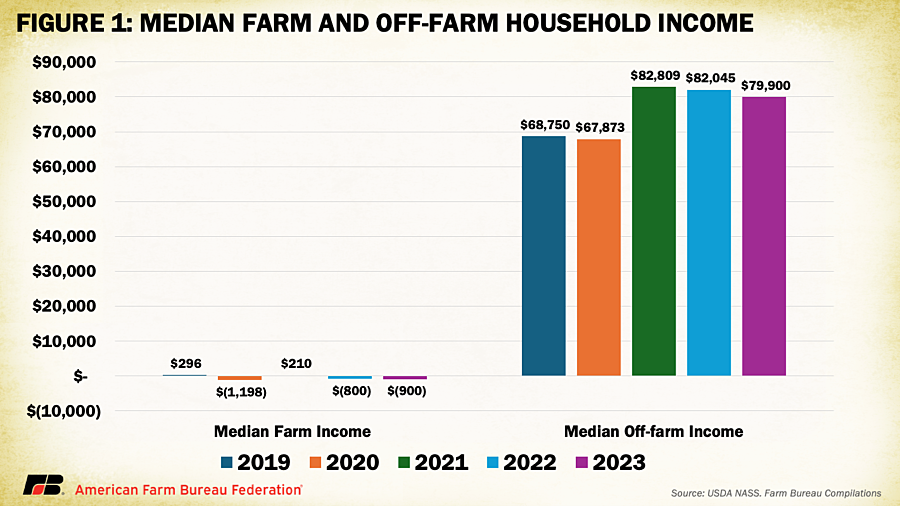

For business owners, long-term optimism is a necessary condition for success, and it’s for sure even more so for farmers, who need to borrow a lot of money and work very hard to make it all go. But there’s another factor that could explain the optimism of American farmers, even in the face of the shifting agricultural trade flows. And it’s that for most of our farmers, most of their incomes do not come from farming.

This is a survey from the American Farm Bureau of thousands of farms, with data over five years from 2019 through 2023. Median income from farming is—zero, may as well say. Off-farm income looks much stronger. In the case of soybean farmers, for example, only 29% of their income is from growing and selling soybeans:

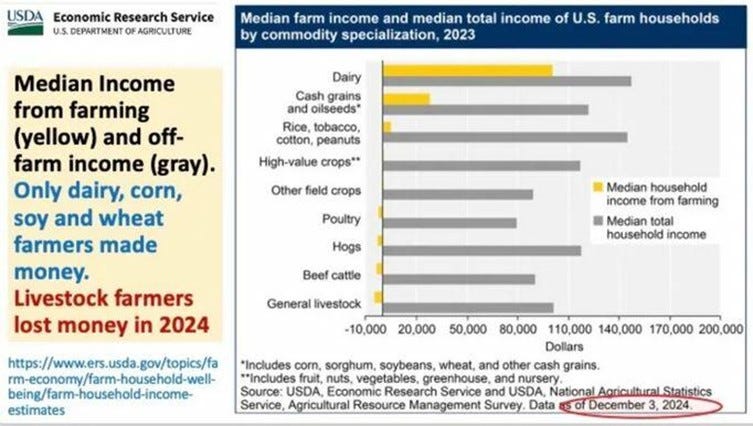

These data are from 2024. The gray lines are income in dollars, total household income. In yellow is household income from farming. Livestock, beef, pigs, and poultry—those farmers are losing money growing food, but doing okay in their non-farming activities. Other field crops and high-value crops we can’t see any yellow at all. It’s only dairy farmers who derive more than a quarter of their income from farming.

And maybe that is the source of the optimism here, an expectation that farmers’ other businesses will improve. Small business optimism in general had a big spike just after the election, and it ticked up slightly, again, in May. So maybe that’s it, and American farmers’ optimism is mirroring the trend of small business owners generally. Because there isn’t any good news coming for American farmers who are now competing against Russians and South Americans.

This is Yueyang Tower, in Hunan.

Be Good.

What are the off-farm incomes? Given the high average age of the American farmer, I would guess social security and retirement funds along with commodity futures trading which many do. Younger farmers often provide services to others, eg hay cutting, fence building, irrigation installation, etc. But I'd like to se a true ranking of income sources.

Why are U.S. farmers optimistic? This is easy to answer. They expect Trump to give them a lot of money in subsidies. They expect farming will be cross subsidised by income from tariffs.