Panic in global metals markets as China rare earth export bans close brokerage hubs

Pentagon races to find new sources of supply for most critical defense systems

Bullets:

China has tightened its export bans on materials with military applications. Its customs office is approving sales only to well-known end users, and for non-military use only.

China also has successfully closed off access to its markets by brokers and resellers. These hubs in Hong Kong, Tokyo, New York, and London report being unable to procure any metals in 2024.

The Chinese bans are pushing metals prices violently higher, and causing panic across defense sectors where these materials are vital for aerospace, ballistics, and munitions.

US miners are reluctant to invest in new production, arguing that China could simply relax restrictions in the future and prices would fall below their cost of production. But industry insiders admit that any production in North America and Europe would fall far short of demand, and would take years to come online.

Report:

Good morning.

China’s export bans on key crucial materials are cascading through our industrial sectors, with deep effects. We shared a presentation last week, where experts conclude that the cost to the US economy for China’s ban of just one of those metals, gallium, would be over $600 billion dollars. And that assumed that just 30% of China’s gallium exports would be cut off. It’s now looking to be much higher than that, and for several metals besides just gallium.

Here are where things stand on gallium and Germanium. Through 2022, the US imported over half of its germanium from China, and just over a fifth of our gallium imports came from China.

Gallium, Germanium, antimony and superhard materials are now off-limits for American importers. And even tighter restrictions on graphite sales are coming shortly. These export bans are in response to US curbs on some memory chips from American and foreign companies, to China. The objective for our semiconductor export bans is to slow down China’s semiconductor and AI industries, some of which have military applications.

Ironically, the Pentagon is even more dependent on Chinese rare earth metals and semiconductors for our own defense systems to work, than the other way around. And panic levels are rising fast, because Beijing is able to clamp down on supplies even further by prohibiting anyone else from selling to the US. It’s the first time China is employing the strategy that Washington has used in the chip wars.

US trade laws, strangely, allow the American government to regulate after-market sales of any equipment, made anywhere by anybody, if it contains a single component that was made in the United States. Now, China is doing the same thing with their raw materials exports. The measures are intended to “prevent international companies from buying Chinese metals, reprocessing them in a third-party country”, and selling to US buyers.

So the end buyers for these materials have some tough choices: either use less, recycle more, or figure out how to produce more. For a brief time, some suppliers were acting as middle-men, but now those markets fear reprisal from China, and traders and processors are backing off. Bloomberg’s source refused to even be quoted by name.

This is a small world, the market for these metals. So anyone buying and selling is already well known, and easy to track, and nobody wants to find out what happens if their company shows up on a Chinese blacklist.

These are “niche markets”, very specialized, and “so much easier for China to stop gallium shipments.” This Japanese company is Japan’s largest importer, and their imports have dropped by half just this year.

Consider how different these markets are, compared to the semiconductor chip sanctions. It’s commonly known now that the chip bans have been a failure, because that is not a niche market. Everyone wants to buy them, and there are lots of companies that make them. They’re easy to carry, in a pocket or briefcase. There are thousands of buyers across the world for semiconductors, who can just resell them to Chinese buyers, or put them into servers and let Chinese companies pay to use them. Even with the hard export bans on advanced semiconductors, they are still in the market, and the prices for them are holding steady.

But in the markets for these metals, prices are ripping higher, and everyone thinks that the supply problems are just starting.

Germanium and antimony have hit all-time records, and gallium is at its highest level in 13 years. The vertical axis is the percentage increase in price since China’s export bans were put on. Gallium and Germanium doubled since last year, Antimony more than tripled.

So the challenge now is to find new suppliers, or get mines and refineries going for these at home. But now analysts are worried about other key minerals that are critical to defense systems, and which we don’t have domestic sources for—tungsten, titanium, and a handful of others.

“Industries that never had a problem before now” are realizing they’ve got one, and they can’t get the metals even if money is no object.

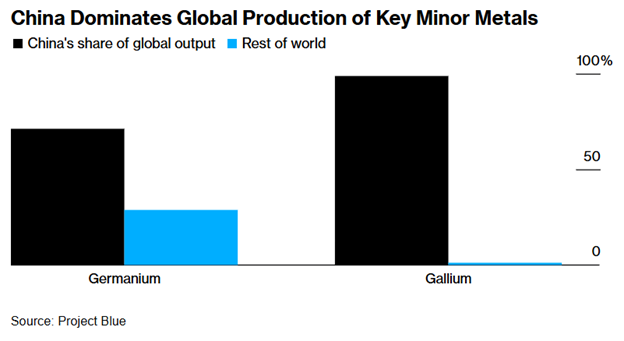

The real issue is the scarcity of the metals, and the fact that China is the bottleneck through which these supplies flow. Global output of gallium is under a thousand tons a year, and China has almost all of it:

“If China wanted to throttle a market, it makes sense to start there, with gallium”. And we’re not even close to the damage could do across these sectors, were they to tighten the screws on all these other materials they have monopolies in. Here’s the production for Germanium and gallium, China compared to everyone else.

In theory, our own miners could just go after producing more. Rio Tinto is a huge mining group, and they’re crunching the numbers on some of their mines in Canada to see if it’s worth it, and another company has some potential in Greece. But here is the problem for those guys: if they invest a lot of money to scale up production, China could just relax their restrictions and send prices down again. The companies need guaranteed prices for long-term contracts.

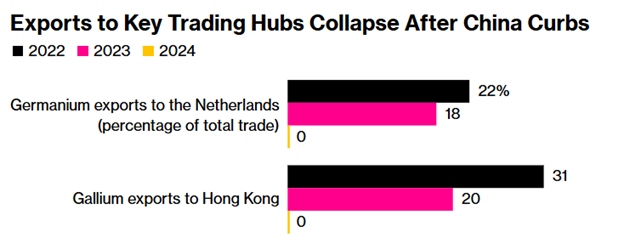

IN the case of germanium, it’s interesting how China’s export bans have taken down the brokerage and trading markets for the metal. Traders in London, Hong Kong, and on Wall Street used to function as market makers, building up inventories at low prices, then releasing them into the market during times of shortage and higher prices, and making money that way. But those traders have been locked out of the markets too, and Chinese customs agents are only approving sales to established end users, and to end users who are affirmatively NOT going to be reselling into the defense industry supply chains.

The storage hubs for these metals are in Amsterdam and Hong Kong, and their trading volumes have dropped to zero, in both metals, in both places.

Following these trading restrictions from China, the White House sent teams to Belgium and the DRC to find supplies for domestic producers, including defense and space contractors. Germanium is necessary to keep satellites in the sky and to tell missiles where to go, and the Chinese have decided that’s maybe not how they prefer to see their germanium used.

We reported on the Antimony problem before too, and antimony truly is in short supply, everywhere, and the global shortage gets worse every time a bomb blows up in Ukraine or the Middle East. There are some deposits in Tajikistan, Myanmar, and Turkiye, but those countries are much more friendly with China, than they are with us.

There’s only one deposit that we know of so far in the US, and the Pentagon has provided funding to a company there to plug the gap for antimony. It’s possible that 30% of America’s antimony demand could be satisfied by the Idaho mining project. Two obvious problems, though, is that 30% is only 30%, and nobody knows where the other 70% is coming from. And of course the mine is years away from producing anything.

A smelter in Montana has been operating at 50% because they can’t get new antimony. When China made their announcement to ban the exports of antimony, the calls from the Defense Department started. It’s hard to find supply, he says. They’ve been on the phone for 4 months trying to find antimony supplies. Every day the Pentagon calls the small handful of people they know, to see if they’ve found new antimony since yesterday.

I have to say, that I’m as cynical as can be. But all of this is surprising, even to me. I admit that I did think, that must be plan for all this, that we had, somewhere, a secret giant reserve of these metals. Something like a Strategic Germanium Reserve, like we have with petroleum, so that if China can’t or won’t sell to us, our satellites don’t fall down.

I never did imagine that our most senior White House and Pentagon officials thought that these metals come from investment banks in Hong Kong or the Netherlands. But they did think that. Then China puts on an export ban—predictably, could add—and suddenly they wake up to a big problem. Uh oh. Maybe someone should go to Africa. See if anyone in the Congo might have a big pile of germanium they’re not using.

Be good.

Resources and links:

Bloomberg, Tiny But Vital Metal Markets Rush to Adjust to Chinese Clampdown

Yahoo! Finance, Tiny But Vital Metal Markets Rush to Adjust to Chinese Clampdown (Abridged, non-paywalled)

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/tiny-vital-metal-markets-rush-133000810.html

China Dials Up US Trade Tension With Tit-for-Tat Metals Ban

China Sets Precedent by Banning Others From Selling Goods to US

De-risking Gallium Supply Chains: The National Security Case for Eroding China’s Critical Mineral Dominance

Explainer: What is 'FDPR' and why is the U.S. using it to cripple China's tech sector?

https://www.reuters.com/technology/what-is-fdpr-why-is-us-using-it-cripple-chinas-tech-sector-2022-10-07/

Play silly games get silly prizes. Or, as I used to say a long time ago when I was in the military 'You want to piss me around well stand by for incoming '. This is the incoming. Zero sympathy.

Thanks for taking your time to share this indebted analysis